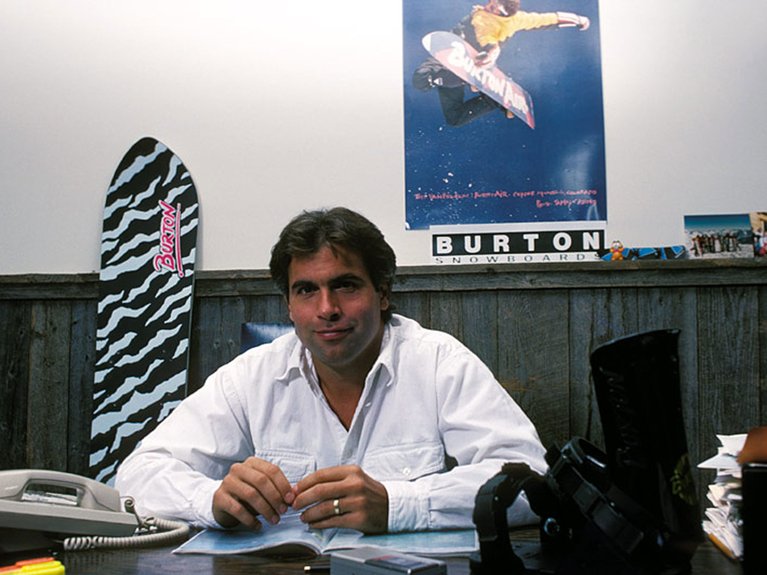

Behind The Scenes: How Jake Burton Carpenter Built Burton Snowboards

"A blank slate of snow. Some would see only empty white space. Jake saw a sport, a community, and a culture. He made something beautiful that had never existed before"

To build Burton and the sport of snowboarding, Jake Burton Carpenter had many obstacles to overcome. His life's challenges weren't just work-related either—he fought back from numerous health challenges to live the life he carved for himself. If you asked Jake what he was most proud of during his lifetime, he always said "perseverance."

Jake's story of perseverance started off with a dream, and a station wagon pointed north to Vermont in 1977. His first challenge: creating the snowboard. Without modern-day snowboard machinery, Jake was left to build everything by hand. Unphased by the feat, he continued to experiment and progress with relentless determination. Over 100 prototypes later, Jake landed on a laminated maple board and named it the Burton Backhill—a narrow design with single strap bindings and a rope handle attached to the nose. Next challenge: convincing the resorts to let riders on lifts.

When Jake had a vision, nothing could stop him. And when the resorts said no snowboarders, Jake lobbied for equality with locomotive force. Those painstaking hours in the barn, hand shaping boards, wouldn't be for nothing. In 1983, he took a fateful run with Stratton Mountain's Ski Patrol that proved his radical wooden planks were no children's toy. With Stratton on board, fellow Vermont resorts Jay Peak, Stowe, Sugarbush, and Killington were quick to follow.

Then it was off to Europe.

In the winter of 1984, Jake and his wife Donna were working desperately to evolve snowboards from their early form to sophisticated modern tools and joined her parents on vacation in Austria. While in the Alps, Jake spent the whole time poking around ski factories to find someone who might produce snowboards with steel edges. Unfortunately, one factory after another turned him down until he stumbled upon Keil Ski, a manufacturer in Uttendorf.

In true Jake fashion, he showed up in the middle of the night ready to get to work. The owner had to wake his daughter up to translate. Jake was determined, and at the stroke of midnight, they shook hands and closed the deal. Shortly after, a prototype of Burton's first modern snowboard was created, complete with ski construction, steel edges, and a P-Tex base.

Jake’s perseverance worked. The new board that he and Keil produced was something completely innovative, and they hoped to show it off at the SIA Ski Show in Las Vegas. But, of course, schedules were tight. Jake was running a little late, so he called in a favor from the factory, asking them to deliver the board in person by carrying it on a plane to the States.

In this case, that guy would be Hermann Kapferer, who happened to run a forwarding company out of Innsbruck, Austria. He stepped up to the challenge and personally delivered the board to SIA on time. That's where Jake and Hermann met—a connection that would change their lives forever.

By 1986, business was booming. Over 1,000 retail shops in the U.S. carried Burton gear, and distribution was just getting started in New Zealand, Australia, and Japan. But that wasn't the only thing heating up. The tension between traditional skiers and punk riders was also boiling over. In 1988, Time Magazine gave snowboarding the title of "Worst New Sport." The credibility of snowboarding was at stake. And just as the sport was beginning to gain traction, Burton was delivered gut-wrenching news. The banks pulled the plug on their business loans because they thought snowboarding was just a fad. Ever the rebel, Jake took it upon himself to prove the big wigs wrong.

And he did just that. With a flourishing team of impressive young athletes and momentum that couldn't be stopped, Jake proved that snowboarding was no longer a hobby for misfits. Instead, it was on track to become an Olympic sport. Jake made the work hard, play hard ethos an art form. But as the sport settled into its place of cultural prominence, Jake was met with a six-letter foe that would be his most formidable challenge yet: cancer. On September 21, 2011, Jake was diagnosed with testicular cancer.

Jake sent a companywide email brimming with optimism. "The bad news is that I have cancer. The good news is that it is as curable as it gets." He was determined to fight and win. Then, in January of 2012, Burton employees received the victory letter they nervously awaited. "It appears my cancer is toast," said Jake. Battling cancer should be the most challenging illness that a person must face in their lifetime. Yet, on March 12, 2015, Jake was informed that he would be almost completely paralyzed from a rare disease known as Miller Fisher Syndrome.

For nearly two months, Jake couldn't move, see, speak, or eat without the help of machines and tubes. His only way to communicate was blindly scrawling notes to loved ones. The notes depicted the full range of emotions felt when faced with a life-altering illness. Each letter illustrated the heart of a man who wouldn’t quit and was filled with love, drive, and inspiration in the face of great adversity.

Once the paralysis lifted, Jake decided to pack as much fun as possible into every single moment. He said exactly what he thought, did precisely what he wanted, and had zero tolerance for bullshit of any kind. The second chance at life was earned through perseverance and belief. When the cancer made its unexpected comeback, Jake put up his final fight and took a bow with grace on November 21, 2019. Then, he headed off to "the other side"—as he called it—to scope out new lines and have even more fun.

It was unstoppable drive and infallible determination that helped Jake change the world and build the sport of snowboarding. When others scoffed, Jake believed. And when times were difficult, Jake battled.

Donna said it best:

"A blank slate of snow. Some would see only empty white space. Jake saw a sport, a community, and a culture. He made something beautiful that had never existed before"— Donna Carpenter.